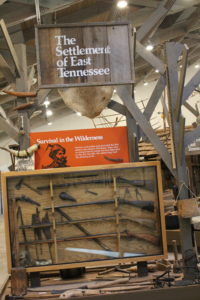

John Rice Irwin spent a lifetime collecting the artifacts of the Appalachian people and although the museum’s founder is now retired, he can still remember just about every auction, every smokehouse and barn he has explored–and every good friend that he has made among the rural folks of Appalachia. Those histories–and the people to which they are connected–are central to his passion for collecting and central to the character of the Museum.

It was the familiar story of the devastating Barren Creek flood–legendary in East Tennessee for churning past the banks of the Clinch River in the dead of night and sweeping many people and hundreds of farm animals to their deaths–that led to one of his earliest purchases. The purchase, made at a local auction, was just an old, worn, poplar horse-shoeing box, but the auctioneer mentioned in passing that it had been fished out of the nearby Clinch River over half a century earlier, following the catastrophic flood.

After that purchase came many others, sometimes at auction, sometimes from making trips over dirt tracks and going door to door. Earning the hard-won trust of rural folk is never easy, and John Rice will tell you that it was his knowledge of and curiosity about old-time farm implements that often opened the door to friendships. But conversations with him begin to draw a larger picture, one where it becomes clear that it was—and continues to be—his admiration and esteem for the ingenuity, craftsmanship, and hardy perseverance of the people of Appalachia that has allowed him to forge relationships of trust and mutual respect.

The purchase of several truckloads of early Appalachian artifacts from Bill Parkey of Hancock County reveals just such a relationship. Bill’s family had lived in Rebel Hollow near the Powell River for generations, settling there before the Civil War, and the old homeplace had a wealth of early tools and equipment that he continued to use for blacksmithing and wagon-making. For years, John Rice had been told that Bill would never part with his beloved tools for any amount of money. The warnings largely were correct, for although John Rice occasionally was able to purchase a thing or two, his trips to “Revel Holler” were generally spent just visiting with his friend. It was only after Bill’s death that his widow called John Rice, saying that Bill had told her never to sell his cherished tools unless it was to “the professor”—because John Rice had “always treated him right.” It is illustrative that John Rice insisted on paying Mrs. Parkey twice her asking price for several truckloads of her husband’s tools.

What grew out of John Rice’s love for this region’s past and its people is an impressive living history that has been nationally acclaimed. It has been featured in the Smithsonian magazine, which said, “it vividly portrays something ethereal—the soul of mountain people,” and it has been named one of only a handful of affiliates of the prestigious Smithsonian Institution in the state of Tennessee.

1950s Period Classroom

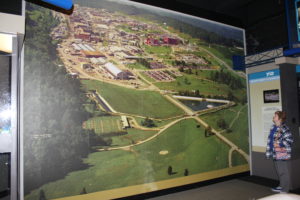

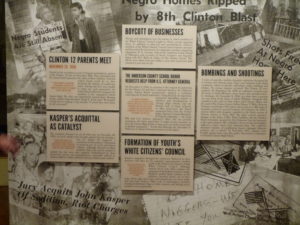

1950s Period Classroom The story begins with the community’s initial constructive approach to the historic event…then the arrival of outsiders with anti-integration propaganda… a week of growing violence… the formation of a home guard… the arrival of the national guard and martial law. Unlike the stories in Arkansas and Alabama, both the city and state governments supported the “Law of the Land”, represented by the desegregation ruling. The city’s white religious and economic leaders, such as the Rev. Paul Turner, a local Baptist minister, allied with the black students and their families, offering them protection in integration and challenging those they led to do the same in the face of rising violence. At one point, Rev. Turner was physically attacked for his heroic stand. The African-American community on Foley Hill became a rallying point for Clinton in the struggle for equal rights for all citizens. In retaliation, white supremacists bombed the high school in 1958, destroying the building, but not halting the progress of equality. Instead, the Anderson County community, citizens and students from Clinton and Oak Ridge refurbished an abandoned elementary school in Oak Ridge- and Clinton High School was back in session in one week, still integrated.

The story begins with the community’s initial constructive approach to the historic event…then the arrival of outsiders with anti-integration propaganda… a week of growing violence… the formation of a home guard… the arrival of the national guard and martial law. Unlike the stories in Arkansas and Alabama, both the city and state governments supported the “Law of the Land”, represented by the desegregation ruling. The city’s white religious and economic leaders, such as the Rev. Paul Turner, a local Baptist minister, allied with the black students and their families, offering them protection in integration and challenging those they led to do the same in the face of rising violence. At one point, Rev. Turner was physically attacked for his heroic stand. The African-American community on Foley Hill became a rallying point for Clinton in the struggle for equal rights for all citizens. In retaliation, white supremacists bombed the high school in 1958, destroying the building, but not halting the progress of equality. Instead, the Anderson County community, citizens and students from Clinton and Oak Ridge refurbished an abandoned elementary school in Oak Ridge- and Clinton High School was back in session in one week, still integrated. Interactive screens will allow you to see the Clinton 12 and others in person and hear their recollections and reflections from interviews by Keith McDaniel, producer of the award winning Clinton 12: A Documentary, which was narrated by James Earl Jones.

Interactive screens will allow you to see the Clinton 12 and others in person and hear their recollections and reflections from interviews by Keith McDaniel, producer of the award winning Clinton 12: A Documentary, which was narrated by James Earl Jones.