American Press Travel News–March 22,–Bob Epstein in Africa–Part 2-Uganda—The most difficult items to eat during our trip through equatorial Africa were: monkey brains, snakes and some lizards. The reptiles were great roasted, but the monkey was just too close to our lineage for us not to feel like we were cannibals. Besides, we didn’t like the gamy taste, or smell either.

I had learned long before I arrived in Africa that the shortest route between two points traveled, or on paper was a straight line. In Africa there are no straight lines or roads. Most of the terrain in Africa called for serpentine roads and circuitous ways. A trek through this land was then, and I understand full well now, a trip through pre history for anyone from the west. Things in the west have changed rapidly, socially, the industrial revolution and all, but in Africa with the exception of the diamond, religious missionary and rubber business interests, few things have changed except for the horror of aids. People that are used to very fast changes in the relativity of the new worlds terms and times would be flabbergasted by the actual snail like pace of change in Africa. People in the hinterlands of Africa are still concerned with, and do things one at a time, with pride and utility. Time in central Africa is not money. People in Africa, not the citified ones, do things, (crafts, building their dwellings, doing anything beyond attending to the daily natural personal hygiene needs) they do their wash in streams and gather brush and branches for cooking fires, they brush their teeth with crushed branch ends the way they have done for untold centuries. Africans, those that have not become accustomed to the white mans ways, still do things one at a time often with pride and high utility. Because time is not money to most of these peoples, a hand carved knife may take days or weeks to craft and speed is not part of the criteria for it’s fashioning. Quality not quantity would seem to describe the craftsman’s philosophy in the hinterlands of Africa.

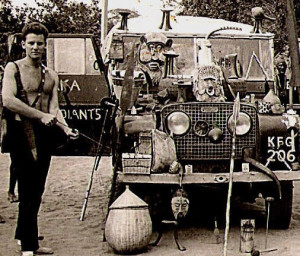

When we traded for such things as knives and finger pianos, or spears or any item an African makes for himself or others of his tribe, manufactured products from the west, such as razor blades, shiny nail clippers or cigarettes. Things such as these that may as well have been made by aliens from another planet were perfect barter and trade item products. For the Africans, it was future shock, they were delighted with chromium products and for us it was museum quality items that would also be treated as priceless. I remember seeing this trade as realistic and fair, even though on cursory notice through western eyes and perspective it would seem the Africans were the ones being taken advantage of, they did and would certainly feel the same way about their good fortune. After all they looked at the transactions from their own perspective. They could make another mask, knife, spear, monkey strap and bow and arrow set out of the natural free material around them. They were sure that the white mans technology would be very difficult if not impossible to reproduce even for the traders from a land of the future.

Africa was not just a place. It was a state of mind. Everywhere we looked, there were things to marvel at. From the style and shapes of African homes and buildings to the dress and customs of these peoples from a lush land, nourished by an equatorial sun and heavy rainy seasons, to the diversity of a people that Thomas Leaky was sure are the ancient ancestors of the birth of Homo erectus or the first man.

Traveling through Africa and experiencing its diverse wildlife, I had no doubt why anyone would not think that this place perhaps was where the concept of the Garden of Eden had come from. Every fruit known to man grows somewhere in Africa, almost every wild animal including the largest land animal the pachyderm and the smallest the Madagascar shrew is indigenous to this continent and it’s environs. There are over 500 different types of snakes, fifty thousand kinds of insects, hundreds of varieties of fish, reptiles and amphibians inhabit the waters, lands and jungles of Africa, not to mention the over 100 different mammalian species that dot the plains, inhabit the trees with over 600 species of birds countless kinds of trees and plants as well as the throwback from the dinosaur age the crocodile. These crocodiles yearly account for hundreds of deaths. People get too close to them as they wash their clothes, take baths and fish in the rivers and lakes and become food for many of these crocodiles. Many crocs reach in access of 20 feet in length. There are hundreds of butterflies and moth varieties besides the aforementioned insect’s numbers, dozens of leech and worm types and you can meet many of them by just taking a swim in any still water pool, lake or river. We did!

We traveled through a land of giant bamboo and trees that seemed to reach the clouds; many of these trees did in the highlands of Kisangani National Park. We took in the fragrance of wildflowers and craned our necks to view the orchids high in the tree boughs. We passed so many natural sights, noticed so many fragrances, all our senses were constantly being bombarded with new, exciting; some just plain scary things that we were on an “info processing overload”, much of the time.

We traveled down a dusty, sometimes muddy road; filled with ruts and high, untamed grasses in the roads center, where tires rarely tread. In the twilight of a late African afternoon we spied a small village off in the distance, and after not seeing another human for days, we decided to stop and visit with the villagers and possibly trade for some fresh fruit, and perhaps a chicken dinner. As we got closer to the outskirts of the village, we saw what we expected were the inhabitants peering through the window openings in their huts. Throughout our visits to villages in the east and central African nations, we’d grown accustomed to the children running out to greet us. However, when we pulled into the village there was no children or people.

Suddenly, we became aware that, what peered out at us was not human. What lived in these huts were baboons. Not just your average plains baboons mind you, but street and town smart ones. Further down that road to Stanley Ville in the Congo, we met other Bantu people who explained the strange inhabitants to us. To our astonishment we learned that the people in the village died out, and the survivors fled from the raging yellow fever epidemic, so when the people left the baboons moved in to take their place.

We saw things in The Congo, in the fields of science, medicine, and philosophy that in terms of our western religion, could not be explained. One example of many with which we experienced, is the time we stayed overnight in a village with no lights, and no concept of electricity. Oil lamps, like in the days of old, was normal, and we sat around a large fire, while the shaman of the village, called on the good spirits to come forth, and the malevolent ones to stay away. This ritual entailed powders to be thrown into the fire, causing flash points, which the shaman was able to attribute to spirit movement and signs from their gods. The people believed in the show and it was hard for me, with all the palm wine I imbibed, not to feel the same way at the time.

APtravelnews-Happy Halloween from AL. & TN.—–